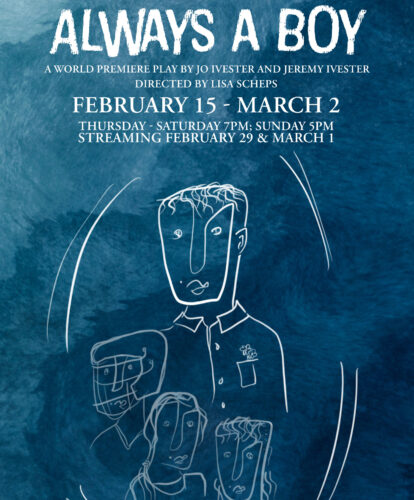

Always A Boy

Always A Boy

By Jo and Jeremy Ivester

Ground Floor Theatre, Austin, Texas

February 15-March 2

This spring, Ground Floor Theatre in Austin presented the world premiere of Always a Boy, by mother-son playwrights Jo and Jeremy Ivester. The play, which addresses the family dynamics of having a trans son, had its world premiere deep in the heart of Texas. This is significant, because Texas is one of the U.S. states that has passed a staggering number of anti-trans and anti-LGBT bills, and its Republican legislators are certainly not finished in their efforts to turn LGBT people into second-class citizens. The advocacy group Equality Texas reports that legislators in Texas introduced 141 anti-LGBTQ bills in the last legislative session, many defeated by activists, though bills limiting gender-affirming care have become law.

Ground Floor Theatre is located just three miles or so from the towering pink marble edifice that is the state Capitol building of Texas, where so much of that political hatred is enacted. Austin, of course, like other large cities in Texas, is a blue island in a sea of red. Always a Boy focuses on the story of Joshua, who was assigned female at birth, and his personal acceptance of his identity, including the struggle for his family’s acceptance.

We first meet a grownup Joshua, dressed in a tuxedo, talking to his mother at a wedding. Behind Joshua are two other actors, one playing Joshua as a child and another playing him as a teenager. The three Joshuas rotate the featured role throughout the play in a series of coming-of-age vignettes, while also serving as a kind of internalized Greek chorus, commenting on what has already happened, or what’s going to happen in the future.

The youngest of the three Joshuas soon takes center stage, overjoyed in the aftermath of their performance in a boys’ football game and anticipating a team sleepover at a teammate’s house.

The family scene is a loving one, and they all celebrate Joshua’s athletic success, and there is no criticism of Joshua’s always wearing “boy’s clothes.” The celebratory mood ends, though, when his mother takes a phone call and reports to Joshua that they’re not invited to the sleepover after all. Because the kids on the team are getting older, only boys are allowed at the sleepover, his mother says, and Joshua isn’t “one of the boys.”

Here the main conflicts of the play are established, which involve Joshua coming to realize, to accept, and eventually to proclaim: “I am a boy; I have always been a boy.” The realizations along the way are sometimes fraught, sometimes delightful. Young Joshua, played with focus and doggedness by Kaden Ono, starts to see his real life and dreams pass by, as when he is not permitted to play on the high school football freshman team.

Later in high school and in college, Joshua is played by Laura Leo Kelly, whose charm and sparkling warmth radiate from the stage. During those years of becoming an adult, Joshua realizes he is truly becoming a man. This Joshua comes out to his best friend Tucker, played by Trace Turner in an even-keeled and likeable performance. It is Tucker, himself a soon-to-be-out gay man, who is Joshua’s first true anchor of support. In a delightful scene of Joshua’s first visit to a queer bar, the two happen upon each other, and kiss.

The family, while loving and mostly sympathetic, grapple with the new reality. His sister Becca, played by Chelsea Corwin, wants Joshua to be a bridesmaid in her wedding. When Joshua comes out as queer, he agrees to be in the wedding, and though the wedding is not portrayed on stage, we learn in a later conversation that Becca was glad to have Joshua there dressed in a tux, standing with the groomsmen.

Seth, Joshua’s brother, played by Max Green, often treats Joshua like his little brother, joking, competing, roughhousing, talking sports. The two share a best friend in Tucker. But Seth mentions that he’s been teased because of Joshua’s interest in football and “boy” activities and clothes. Seth also doesn’t react as Joshua would hope to a story about a trans guy he knows from college. Seth and Becca are understanding and accepting whenever Josh tells them a little bit more about his own truth. For many kids, their siblings are the nearest and natural audience for confessions and shared secrets of all kinds, and coming out to siblings can be easier first step before approaching parents.

In perhaps the most delightful scene in the play, a drunk Joshua, home from that first night at a queer bar, realizes that he likes men. Laura Leo Kelly’s tipsy, giggling performance here, witnessed by and shared with Becca and Seth, is the type of “don’t tell mom and dad” scene many adult siblings will look back on and remember with a smile.

Joshua’s dad, played by Nathan Jerkins, wants to do the best he can for his child. When Joshua announces that he wants to have top surgery, though, Dad balks. When Joshua wore boy’s clothes as a child, or played sports, Dad never objected, but surgery is a step he cannot understand Josh making. He comes around in the end, however.

While most of the emotional work of the play takes place among the three Joshuas (or all of them together, in their chorus-like role), the journey of his parents is its most contentious near the end, as Joshua’s mom convinces her husband of the importance of loving Joshua all the way, as a boy and a man. We return to the opening scene, when we see at last whose wedding we were witnessing. It’s Joshua’s wedding; he is marrying Tucker. But it’s not Tucker who Joshua shares the stage with at this moment; it’s his mom, at which point she finally comes to a full realization that her son has always been a man.

The story we’re witnessing, after all, is a shared, dual journey. Jo and Jeremy Ivester wrote the script together, based on Jo’s memoir Never a Girl, Always a Boy, and Jeremy plays basically himself, adult Joshua. It’s a remarkable mother-son journey and collaboration. The play is an enactment of something that is rare in the media these days: the joy of being trans. In an age of brutal anti-trans legislation and scapegoating, Always a Boy can be seen as a political statement and an antidote to cynicism.

Brian Fehler is a writer and professor currently teaching at Texas Woman’s University. He is a member of the Human Rights Commission’s DFW Federal Club and a recent graduate of Equality Texas’s fellowship program.

Brian Fehler is a writer and professor currently teaching at Texas Woman’s University. He is a member of the Human Rights Commission’s DFW Federal Club and a recent graduate of Equality Texas’s fellowship program.