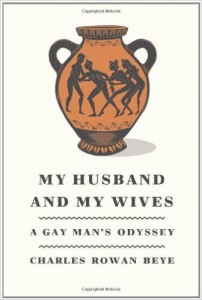

My Husband and My Wives: A Gay Man’s Odyssey

My Husband and My Wives: A Gay Man’s Odyssey

by Charles Rowan Beye

Farrar Straus & Giroux

256 pages, $26.

CHARLES BEYE’S MEMOIR begins like a l9th-century novel: the narrator’s second wife, to whom he has not spoken in years, is dying, and his children are begging him to visit her. Not only does he refuse, but when she dies he suspects that she willed herself to expire just to avoid his visit.

Given the opening, it’s no surprise that the memoir that follows “is in one way or another addressed to her … a woman with whom I had what I remember as a delirious sexual relationship and who bore me four wonderful children, two boys and two girls,” though “I never stopped having the strongest possible desire for males of about my age, a desire I tried to realize whenever I could. Now that the whole thing is nearly over—I’m more than eighty—I ask myself, What was that all about?”