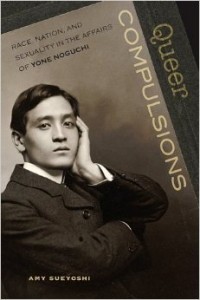

Queer Compulsions: Race, Nation, and Sexuality in the Affairs of Yone Noguchi

Queer Compulsions: Race, Nation, and Sexuality in the Affairs of Yone Noguchi

by Amy Sueyoshi

University of Hawaii Press

232 pages, $40.

IF THE SURNAME Noguchi sounds familiar, it’s probably because of Isamu Noguchi (1904–1988), the versatile and successful American artist who achieved worldwide fame not only as a sculptor, urban architect, set designer, and furniture designer, but also as a jet-setting playboy whose many romantic dalliances with movie stars, among others, often made headlines. But it is the artist’s father, Japanese-born writer Yone Noguchi (1875-1947), who is the subject of Amy Sueyoshi’s study in Queer Compulsions. Though the elder Noguchi is largely unknown today, long since eclipsed by his much more famous son, he was a literary star in America and Japan in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. As Sueyoshi chronicles in her study, his fame was largely the result of many astute and unscrupulous manipulations, and his story illuminates larger issues of imperialism, racism, and sexual politics.