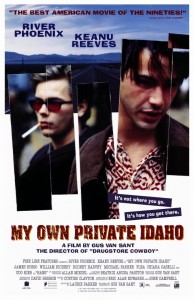

My Own Private Idaho

My Own Private Idaho

Directed by Gus Van Sant

NEAR THE END of Gus Van Sant’s 1991 film My Own Private Idaho, Scott Favor, played by a young Keanu Reeves, looks out from a limousine window to see his friend Mike Waters, played by River Phoenix, asleep on a sidewalk. The scene represents a significant plot shift in the film: Favor—who really is favored by the fates—leaves behind his days of rebelliousness and street hustling and assumes the mantle of privilege he had previously shunned. Watching that scene now, nearly fifteen years after the film’s original release, one can’t escape its irony and poignancy. Just a few years after starring in Idaho, Phoenix died of a drug overdose in front of an L.A. nightclub. Reeves, who was a close friend of Phoenix and who has admitted that the actor’s death affected him deeply, has since gone on to enjoy his fair share of success as an actor.

Van Sant’s vagueness with regard to what Idaho is “about” is understandable. In many ways, the actual story told in My Own Private Idaho seems less important than how it’s told. Some of the most stunning information about the characters is almost glossed over, such as the revelation that Mike is the result of an incestuous relationship between his mother and his older brother Richard. As he had in his films before Idaho (such as 1989’s Drugstore Cowboy) and in films since (such as last year’s Elephant), Van Sant brings a level of poetry to his films in which the silence speaks as much, if not more, than the words. What seems most significant in Idaho is the mood of the film. Van Sant’s sweeping vistas of the fields, roads, and skies of the American Northwest; his loving, witty, and humane portrayal of the street hustlers and their pathetic, lonely customers; and his wonderful blend of humor and pathos, of high art and pornography—all combine to create a uniquely elegiac, lyrically beautiful film.