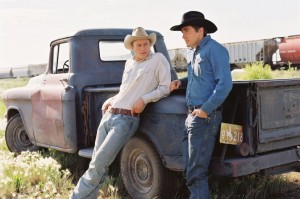

STANDING IN LINE for Brokeback Mountain the afternoon it opened in Washington at a little theater near Dupont Circle, I saw two kinds of people: silent gay men of a certain age, and clusters of laughing college students. For the former, the movie we were about to see was personal, crucial; for the students, I guess it was—cool. The college students were happily chattering away. The gay men were lined up, in our individual solitude, waiting to weep. As I counted the thinning hairs on the head of the man in front of me, I thought: The sadness of Brokeback begins outside the theater.

There had been so much buzz and praise for this film that I was proudly prepared to be the first kid on my block to hate the picture; and, to be honest, it was not very long after it began that I found myself wishing Fred and Ginger would burst onto the set and tap dance across the screen, like Dom DeLuise at the end of Blazing Saddles. There were even times when I found myself looking at my watch, or thinking the movie should end here. The relentless bleakness, the one-note, unrelieved gloom, made me impatient. Then, the last twenty or 25 minutes, the whole movie rose onto another plane altogether, and when it ended I wondered how most of the audience was able to stand up so quickly, gather their coats and leave. A few of us remained in the dark theater, on our feet, listening to Willie Nelson sing “He was a friend of mine,” watching every single credit unroll until only the corporate logos remained. I was relieved to know it was already dark outside, glad I did not have to walk past a gauntlet of people waiting for the next show. I was so upset I went home and phoned a friend in New York who had seen it the previous week. It was only when he said, “I don’t want to bring you down, but…” that I could tell I was in some sort of semi-hysterical reaction that was probably explained by mid-life crisis or the Christmas blues I had been hoping to escape when I went into the theater—i.e., what one brought to the work of art as well as the work of art itself.

Indeed, the next person I phoned—a man who’d told friends at the gay gym afterwards about the movie—said he wasn’t sure younger gays would get Brokeback, if they would not dismiss the whole storyline because they couldn’t understand why anyone would repress his homosexual longings. At a later screening, however, while watching a Brokeback audience leave the theater as I stood there waiting for a ticket, there were several young gay men wiping tears away. (I began to think of going to the theater every hour just to watch the audience walk out.) But that shouldn’t have surprised me. Brokeback Mountain is not only a movie about a time when homosexuality was murderously taboo, but also about the way a man can waste his life, not do what he wanted to, miss his chance, or fail to know how much he loved someone. Its power comes not just from doomed romance but from a theme that runs through some of the greatest, and darkest, American literature (The Great Gatsby, Death of a Salesman, An American Tragedy)—the dream we fail to realize.

Indeed, the next person I phoned—a man who’d told friends at the gay gym afterwards about the movie—said he wasn’t sure younger gays would get Brokeback, if they would not dismiss the whole storyline because they couldn’t understand why anyone would repress his homosexual longings. At a later screening, however, while watching a Brokeback audience leave the theater as I stood there waiting for a ticket, there were several young gay men wiping tears away. (I began to think of going to the theater every hour just to watch the audience walk out.) But that shouldn’t have surprised me. Brokeback Mountain is not only a movie about a time when homosexuality was murderously taboo, but also about the way a man can waste his life, not do what he wanted to, miss his chance, or fail to know how much he loved someone. Its power comes not just from doomed romance but from a theme that runs through some of the greatest, and darkest, American literature (The Great Gatsby, Death of a Salesman, An American Tragedy)—the dream we fail to realize.

That must be why screenwriter Larry McMurtry snapped up the rights to the Annie Proulx story when it appeared in The New Yorker. Brokeback fits right into McMurtry’s view of the West as something poor, bleak, forlorn: the anti-myth. The romance depicted in the first half-hour of Brokeback Mountain recalls the idylls of Theocritus—but here the shepherds’ love erodes into the grim poverty, homophobia, and hardscrabble bleakness of life in the modern American West.

I never even bothered to finish the story by Proulx when I saw it in The New Yorker. Oh, I thought, gay cowboys—clever!, and moved on. Reading the story after seeing the film, I remained skeptical. Written in a kind of faux-gruff, stoic, cowboy style (Ennis’ voice), it reads, to me, more like a film treatment than a story. In fact, virtually everything in the tale (except a few key lines, a friend pointed out, that emphasize the erotic nature of their bond) is in the film. Many of the climactic speeches in the movie are right there, word for word, even if what is heart-rending in the film seems flat on the page. While McMurtry says Proulx’s “masterpiece” is an exception to the rule that great books make bad movies, it still seems to me more an example. Proulx herself says the movie “really enriched the story. Instead of a little canoe, it became an ocean liner.” But praise be to Proulx for inventing this story, even if a prose writer watching Brokeback must end up in awe of the power of images and music.

Reactions to the film have run the gamut, and I became a bit obsessed with asking people what they thought. Like the narrator in Proust who judges people by their opinion of the Dreyfus case, I began to think how you felt about this movie described your character. This is silly, of course; a friend accused me of putting him on the bad team because he found fault with the film, and reminded me that reactions were not either-or but on a spectrum. It was my own reaction I should have wondered about. One can discuss works of art as to whether they’re well-made or poorly made. Yet I wondered why some people were devastated by the movie and others not. Some people were annoyed by the plot. One couple I know in San Francisco saw the movie in different ways: the younger one glad he had escaped that life, the older (a divorced father like Ennis) so depressed he had to go to bed for a day afterwards. Surely what one brings to Brokeback explains one’s feelings about it.

One friend I spoke to said the movie was okay but he had not been especially moved, in part because he thought the plot was one that gay people have moved beyond at this point. The next friend sent an e-mail listing all the lines in the story that had been left out, he thought, in order to downplay the erotic specifics of the story. (It was a convincing brief.) Still another said he kept wondering, as the movie unfolded, “Why don’t they just pack up and move to San Francisco?”—a question answered when his friend replied: “Because they were drinking too much to think of it.” An old friend who used to herd his grandfather’s sheep up into the mountains of Colorado pointed out that even Ennis’ and Jack’s clothes were too new—that they should have been worn, faded, covered in dust and dirt. Of course, Brokeback Mountain is a gorgeous Hollywood movie, with very handsome leads. In the Proulx story, Jack Twist is so buck-toothed he draws blood during the great face-mashing scene at their first reunion, and becomes “swollen in the hams”—buttocks—as he ages. When The New York Times ran a story about “real” gay cowboys in Wyoming soon after the movie’s release, the photographs of the brave men willing to have their images made public were evidence that real cowboys tend to look pretty homely.

Another discrepancy: most gay stories, critics have pointed out, are urban, and it is ironic that a story about two men who marry, have kids, and ride horses for a living should have such an impact on gay men who have done none of these things. Brokeback Mountain is a very butch addition to the tradition of The Boys in the Band. (When was the last time you slept with a man who beat up bikers for talking dirty in front of his wife and daughters?) The New Yorker went so far as to say the “gay cowboy movie” was neither gay nor a western. One gay male friend, and two women who reviewed the movie in The Washington Post and The City Paper, said the movie had not convincingly portrayed the passion on which the story was based. Gene Shalit called Jack a “sexual predator.” Then there were the jokes. The idea of two cowboys in love apparently made the culture nervous. How else to explain the wisecracks that followed the movie by Jay Leno almost every night, David Letterman’s “Ten ways to tell if a cowboy is gay” list, the Times’ clumsy parody that turned Jack and Ennis into two queens in The Sound of Music? Finally, there was the cartoon in The New Yorker showing two lovers in a bedroom, one handing a cowboy hat to the other, who says, “And what if I don’t want to be Jack or Ennis?”

Perhaps the sadness in this movie that The Washington Post critic deprecated as “self-serious” made people nervous because the whole achievement of Brokeback is to make this love serious. It’s important to stress that, whatever else it is, Brokeback is a love story. That’s the source of its power: as old as Romeo and Juliet. This movie, as Frank Rich pointed out, is not based, like Philadelphia or Angels in America, upon AIDS. It’s about two men who reduce the whole world to one another. (Some of the most painful scenes belong to the marvelous Michelle Williams as Ennis’ wife.) Proulx has said, perhaps too confidently, that the only men who would not go to this movie were those “insecure about themselves and their own sexuality.” In other words: “Jack and Ennis would have trouble with this movie.” (Or, it occurs to me, the men who killed Matthew Shepard.) Brokeback is not Will & Grace or any of the other things we’ve had until now. Brokeback Mountain, it seems to me, in some strange way provides gay characters what only AIDS has given them till now: dignity—in part because they’ve been inserted into the heart of American masculinity (the western cowboy), even if, as Manohla Dargis pointed out in the Times, the two men are really shepherds. That’s true. They are shepherds (work, Proulx says, that cowboys look down upon), but they lasso each other and ride horses and shoot rifles and enter rodeos, and that’s cowboys to most folk.

That a love story should be told through two cowboys is the real shock here, even if you disagree with the claim that cowboy movies have always had the homoerotic issue simmering under the surface—or on top, in Warhol’s Lonesome Cowboys. The cowboy is our national icon. (This is why some historians have made an effort to show that there were African-American cowboys.) It’s our central self-image. In Brokeback Mountain, a director raised in Taiwan, an Australian lead, a Mexican-American cinematographer, and an Argentinean composer have made a western that put gays into the American narrative.

Most superior works of art, however, have more than one element, and Brokeback is such a work. The story of these two loser ranch hands is also a film about adultery, poverty, the miseries of family life (it was important to have women in this story, Proulx said), dreams one never realizes, wasted lives, the attempt to conform, friendship, and isolation. While the love between Ennis and Jack starts out as an idyll—as bucolic as Theocritus—it does not remain that way for long. The “urban critics,” Proulx writes, dubbed this movie a tale of two gay cowboys. No. It is a story of destructive rural homophobia. Although there are many places in Wyoming where gay men did and do live together in harmony with the community, it should not be forgotten that a year after this story was published Matthew Shepard was tied to a buck fence outside the most enlightened town in the state, Laramie, home of the University of Wyoming.

It is that theme that drives the movie and provides the contrast with the pastoral love. The editing and the score follow a single pattern throughout, alternating the magnificence of the mountain scenery (guitar and orchestra) with the squalor of the men’s domestic life (the whine of country-western songs), the homophobia that requires the repeated escapes, followed by inevitable return. The whole movie is structured on this schism between the ideal and the real. Ennis lies in the street, being punched and kicked by the driver he has attacked. Cut to the breathtaking ridge on which Jack and Ennis are riding to their rendezvous.

Indeed, everything about the relationship between Ennis and Jack is both idealized and utterly true to life. Passion is very much here—a passion that will make the sex obsession many gay men settle for seem so much less. But what’s unsettling is the context. What’s threatening to some about the movie is the way it blurs friendship and Eros. Jack and Ennis are both best friends and lovers, fishing buddies who bring home no fish. Nothing is so touching as the way Jack prefaces his remarks to Ennis with the word “friend” (or the Bob Dylan lyrics Willie Nelson sings over the credits in “He Was a Friend of Mine”). This most masculine, most American, of themes (“Come back to the raft, Huck honey”) is at the movie’s core.

This may also be why one review complained that Brokeback is ahistorical: the romance takes place in a vacuum, with no reference to anything outside the relationship. The longing of Jack and Ennis for one another, though set in the early 1960’s, seems to unfold in its own little world—the way love does, actually. I suppose, had Ennis and Jack been allowed to live together, or grow old, their romance would have devolved into arguments over dish washing, channel changing, drinking, and depression. Maybe they would have moved to San Francisco, or started doing threesomes. But in this movie they do not. Their love lives on after you leave the theater because it was never obtained. (There is at the end one crushing revelation that Jack had transferred his dream of running his folks’ ranch with Ennis to a man in Texas; that news is just one more tiny nail in the coffin of Ennis’ loss.) Yet it’s this that makes Brokeback so moving: it’s a never-resolved argument between two men, one who wishes to live freely with the person he loves, and one who believes society will not let them, having witnessed something as a child that instilled that message in him in a fearful way.

Brokeback Mountain indicts both kinds of homophobia: the external and the internal. As awful as the homophobes are who litter the film (from their first boss, to the rodeo clown who rebuffs Jack’s offer to buy him a drink, to his father in the final scene), it’s equally about gay men’s self-censorship, their internalization of what is expected of a man. That’s why Heath Ledger’s character dominates the movie. One reason Ledger’s performance has been praised so much more than Gyllenhaal’s (though the latter’s is just as good) is that we’re with him at the end, and it’s his moment of self-recognition that provides the traditional climax of Greek tragedy—when the hero finally learns what his failure to see and understand has cost him and others.

You could argue, I suppose, that Brokeback is a wallow in self pity, like most country-western songs—a lot more sentimental than Warhol’s Lonesome Cowboys, since the whole movie rests on that most profound of human dreams: What Might Have Been. One critic said it is “a cowboy’s version of Imitation of Life” (the Douglas Sirk melodrama). In other words, this is just another middlebrow tearjerker based on the usual stereotype: love that doesn’t work out, done with gay men, guitars, and horses. (We have a strange sensitivity to stereotypes in this country when it comes to the portrayal of minorities: this means we are not allowed to portray an aborted gay love affair because in reality most gay love affairs are just that.) Brokeback Mountain reminded a therapist I know that all of us long for attachment. And surely this movie is about that theme, the longing for love; and the failure of real life to live up to our ideals. But in the end Brokeback Mountain is not sentimental; it’s tragic in the Aristotelian sense—because Ennis is left alone to recognize the price of his inability to have a life with Jack. It’s Ennis’ stoicism, his frustration, his rage and sorrow, his solitude that follow us out of the theater. The only time Jack and Ennis are happy is when they’re together; the rest of the time, they’re each alone in the world. It’s only when they are out of the world (in the mountains) that they can be a pair.

Yet most of us, despite The New Yorker cartoon, are both Jack (longing for love from a withholding man) and Ennis (withholding love from someone else). In talking about the film with friends, it impressed me that we talked about them as if they were real people, and debated things like who was top and who was bottom, and whether Jack was gay, but Ennis gay only with Jack. One of the truthful things about the two sex scenes in the tent—a place the camera stayed out of for the rest of the movie, to one friend’s consternation, but then how much gay sex can a mainstream audience take?—is that the first time, Ennis is on top, and the second, Jack rolls onto Ennis. That’s gay life. We are constantly in flux between the two—Jack the bottom and Ennis the top, Jack the romantic and Ennis the realist, Jack the optimist and Ennis the pessimist—though the one thing we constantly struggle with is the message that Ennis’ father passes on: that two men do not lie (or live) with one another.

Fathers, or their absence, strangely haunt this movie. One of the most touching letters Proulx got, she said, from a father who’d read her story, contained this line: “Now I understand the kind of hell my son went through.” But in this movie—which is surely about fathers and sons—no father shows any sympathy. In fact, both Ennis and Jack seem to be fatherless from the start. Ennis lost his father when still a child; Jack’s father never went to see him in the rodeos or passed on any of its secrets, and at the end provides the final homophobic cruelty. When they grow up they both have kids. In the story Ennis tells Jack he wishes for a son; but it’s Jack whom we see driving the farm equipment with his son on his lap. Ennis has two daughters who adore him, but he’s the silent, stoic Marlboro Man, unable to express affection, the man whose attention everyone craves, in other words, the American Dad. And it’s his dilemma that’s so shattering, because he is trapped in the fear that his own father passed on to him.

Yet we feel liberated by the spectacle. Ah, we say, that’s the problem! We need only fall in love again and get over our fears. Some movies give us a kind of courage, make us want to change, which of course is much easier to do onscreen than in real life. Brokeback Mountain is one of those movies. After years of watching gay subject matter come into the light, it was unexpectedly thrilling to see one of the oldest genres of American art, one of its fundamental tropes, being used to tell what it feels like to be gay. Trying to analyze this film is to reduce the claims it has on one’s feelings; it’s pointless to do so, because, like all great movies, as Pauline Kael said years ago, it just sweeps over you. We will see Ledger and Gyllenhaal in other films. (Look how the former’s Casanova followed so quickly his Brokeback.) They, and we, will move on. But in some films characters exist, independent of reality. They live eternally in that particular movie, and the movie lives in us.

Although Brokeback is too painful a movie to watch many times, the curious thing is it makes you want to fall in love again. Instead, one listens to the soundtrack, which alternates between the pastoral beauty of Gustavo Santaolalla’s theme on the guitar—so spare, so haunting—and the raucous, messy world of the bars, where Matthew Shepard met his killers. I’m not sure why Brokeback is so moving. But in the end I think it has something to do with its being what McMurtry called it: “a tragedy of emotional deprivation.” This is surely a universal experience, but at a certain point in life most gay men seem to conclude that it’s the particular fate of being gay.

Andrew Holleran’s latest book, Grief: A Novel, will be published later this year (Hyperion).