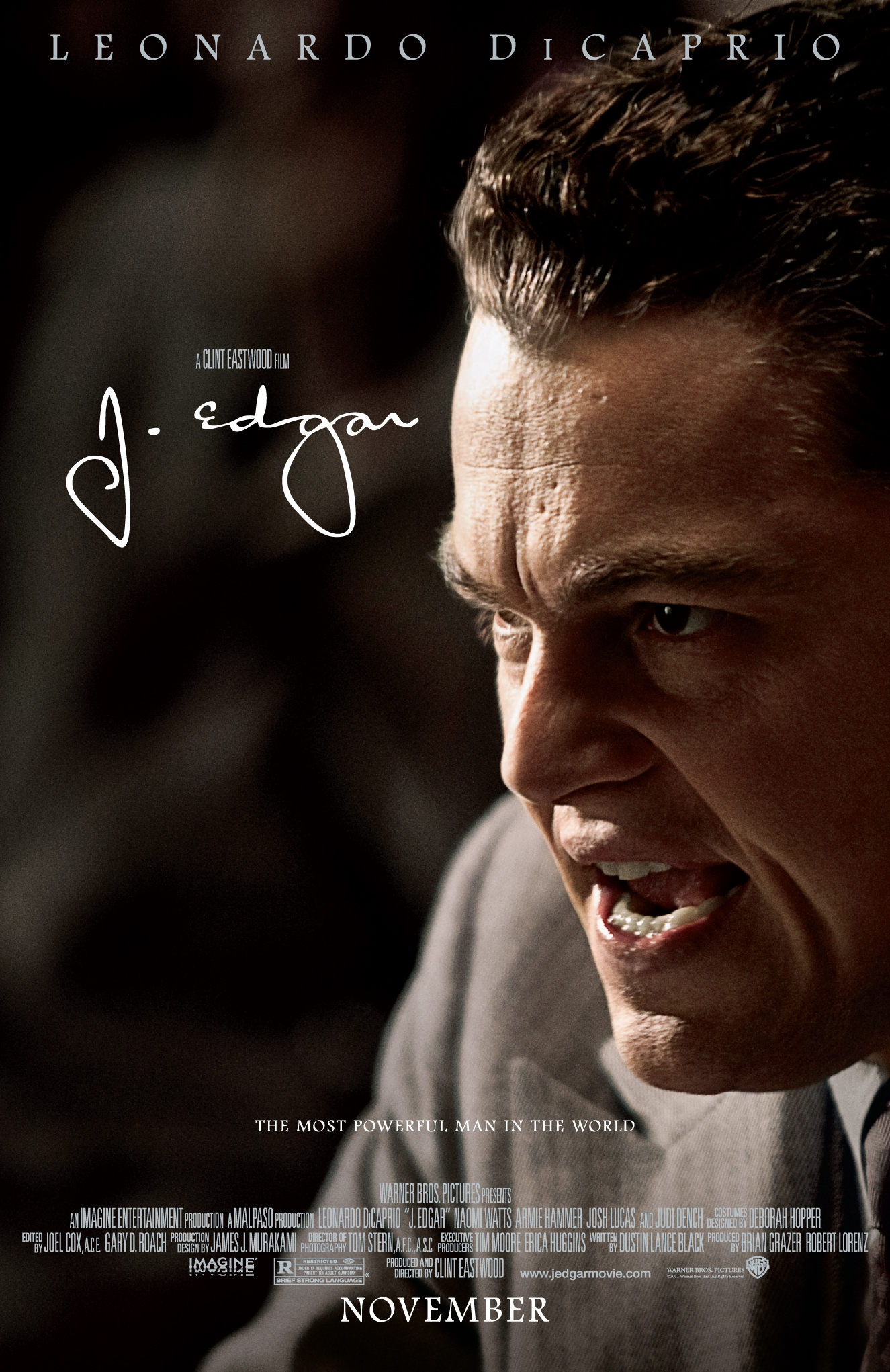

J. Edgar

J. Edgar

Directed by Clint Eastwood

Written by Dustin Lance Black

Imagine Entertainment

THERE’S NOTHING really wrong with J. Edgar, a film directed by Clint Eastwood and written by Dustin Lance Black (who wrote the screenplay for Milk, another recent gay biopic). It’s atmospheric, it’s well acted, it covers an interesting sweep of American history, and it effectively dramatizes the relationship Hoover had with his lifelong companion Clyde Tolson—and, more important, the one he had with his mother. It’s just that one still spends a significant portion of this movie simply waiting for it to end.

The film opens with a truly shocking scene that sets the tone for Hoover’s entire career and provides the key to his character: a plot by anarchists to blow up the house of his boss, the U.S. attorney general, along with several other prominent Americans, in 1919—when Communists and anarchists like Emma Goldman hoped to overthrow the government. Hoover was obsessed with Bolshevism forever after. Years later, when Robert Kennedy asked him to turn the FBI’s attention to organized crime, he would not surrender this obsession. Like Senator Joseph McCarthy, Hoover believed that foreigners were trying to destroy America; unlike McCarthy, he did not equate Communism with homosexuals. In fact, it is now thought that Hoover, judging by his relationship with his right-hand man Clyde Tolson, was one himself.

Whether this was so is one of the subjects of this movie. Nowadays there is something irresistible about the idea of the crime-fighting G-man  being a big queen.

being a big queen.