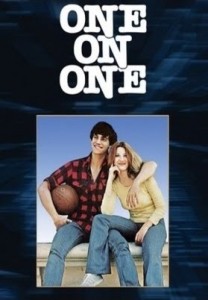

I WAS A LATE TEENAGER in 1977 when I saw the not-much-older Robby Benson star in the newly released One on One. I bought a ticket to the 2:10 showing at the Varsity Theater in downtown Evanston, Illinois, and when the film ended at 3:48, I stayed on in my seat for the 4:10 showing, looking up to the twinkling starry ceiling for the occasional shooting star, and then remained for the 6:05 screening, by the end of which the moon had risen in the theater’s sky and outside on Sherman Avenue. Of all the team sports, basketball, the subject of the movie, was, and remains, my least favorite and yet it compelled me for those five-plus hours.

I WAS A LATE TEENAGER in 1977 when I saw the not-much-older Robby Benson star in the newly released One on One. I bought a ticket to the 2:10 showing at the Varsity Theater in downtown Evanston, Illinois, and when the film ended at 3:48, I stayed on in my seat for the 4:10 showing, looking up to the twinkling starry ceiling for the occasional shooting star, and then remained for the 6:05 screening, by the end of which the moon had risen in the theater’s sky and outside on Sherman Avenue. Of all the team sports, basketball, the subject of the movie, was, and remains, my least favorite and yet it compelled me for those five-plus hours.

In high school gym class, I never understood the offense called double-dribbling, a violation Robby Benson (aka Henry Steele) never committed in his movie (the script for which he co-wrote with his father). In real-life gym class, every time I tried to move along the court, slapping the pinging ball to the floor, the coach’s whistle would shriek and I’d be accused of double-dribbling, a crime I didn’t even know how to deliberately commit, but kept doing. Not long before seeing One on One, I had been made to endure the slave-market treatment of being paraded before the team captains, who, per 1970s political correctness protocol in my high school, always seemed to be the toughest black kids, all of whom took their basketball seriously. When it was down to just three of us left to be chosen, with the teams almost complete, one of those captains muttered aloud about me, eyeing my pale skinny flanks, “I don’t want that one, he looks dead.”

But Robby, galloping along that court on screen, his shelf of perfect black hair feathered over his ears, Lake Michigan-blue eyes, matching yellow uniform (with black piping at the neckline of the sleeveless top), and garbed in the high-riding, hugging-the-thigh basketball shorts of the day, finished with ankle-length white socks, was so alive for me that I couldn’t leave the theater. I had to keep witnessing the sheen of sweat that made him glisten on screen, see the way his hair forked against his forehead, hear the rasp of his voice. Then and now, no one was more beautiful on-screen to me.

At the time, I knew already that I was gay and was completely comfortable with it, unlike Robby in the prior year’s film Ode to Billy Joe, in which, as the teenage namesake character, he tearfully admits to a girl in love with him, “I ain’t alright. … I have been with a man, which is a sin against nature, a sin against god. I don’t know how I coulda done it.” In the film, he would commit suicide by jumping from the Tallahatchie Bridge.

That had been the first time a boy near my age admitted to doing what I had wanted to do. The only other overt “gay” movie reference I knew up to that point was in Deliverance, which I had gone to see with my high school buddies at the Valencia (my town’s other downtown theater, noted for its Spanish Baroque motif and drifting El Greco-esque clouds  in its sky ceiling). My friends already knew I was flirting with the idea of being bisexual, a misnomer in both senses of the word, but a safer way of admitting something. But to see a man-on-man rape committed by a deranged hillbilly humiliated me. (I cringed every time one of my friends quoted the line where Ned Beatty is made to “squeal like a pig.”) I was fearful that they thought such an act on screen might have appealed to me or was even something I might be doing. But my friends were an enlightened lot and my worries were unfounded.

in its sky ceiling). My friends already knew I was flirting with the idea of being bisexual, a misnomer in both senses of the word, but a safer way of admitting something. But to see a man-on-man rape committed by a deranged hillbilly humiliated me. (I cringed every time one of my friends quoted the line where Ned Beatty is made to “squeal like a pig.”) I was fearful that they thought such an act on screen might have appealed to me or was even something I might be doing. But my friends were an enlightened lot and my worries were unfounded.

So resonant was Robby’s plea to reckon with his homosexual desires as the character Billy Joe, the bridge looming all the while like an ominous villain, that I was never able to think of the actor as not being gay. (He’s straight, married, has children and is now, gasp, nearly sixty years old.) When Benson starred in the 1977 TV movie version of Our Town as the main character, George Gibbs, and offered to carry Emily’s books through Grover’s Corners, I felt an instant ache for the friend he left behind in the opening scene, a lad named Bob. In the movie, George and Bob are teammates. At one point they’re seen walking together at the end of a school day, when suddenly George spots Emily. He leaves Bob behind, mid-conversation. Bob lingers in the background. We all remember that same feeling in high school, when your best friend, someone with whom you were inseparable, with whom you’d share sleepovers, would suddenly get a girlfriend and abandon you.

I think most people who fall in lust with a movie star do so because that figure is unlike anyone in their real life, some invented ideal of beauty and sexiness. But Robby in One on One was so eerily like someone I loved in real life that to see him on-screen was to see a version of my love, a boy named Chris, who was my age and visiting my hometown for one school year from his native Montreal. Of course, I could look at Robby on-screen for as long as I wanted and never raise suspicions of desire. Ironically, I met Chris the first day of my senior year of high school on the basketball court. He chose me as my one-on-one gym partner and our first interaction involved my straddling and holding down his legs as he did sit ups, huffing and puffing and raising his face nearly to mine something like 55 times.

The only sport I’ve ever been good at is golf, something I owe to Chris, who was a master player and who taught me the proper way to swing. In order to be with Chris as much as possible, even beyond the hours of school, I played a few holes of golf with him every morning before and after school. We would later phone each other while doing our homework in our mutual houses across town from one another.

I watched One on One shortly after Chris left my town to return to Canada. Our friendship had always seemed charged with a sexual frisson that was nearly acted upon only once. Stereotypically enough, it was the night of the senior prom. Despite Chris’ popularity as a star hockey player and golfer, and his being as beautiful as anyone in the school, he announced to me that he and I were to go to Six Flags amusement park on the sacred night. Throughout the evening at the park, Chris and I had shared a seat on every ride. On the Ferris wheel, we were put into an enclosed cage-like gondola with two girls our age who had been waiting in line, far behind us. The female operator purposely chose them to ride with us. “You all need to be together,” she said after securing our seat belts and clicking the door shut.

Although Chris didn’t seem to notice the girls, looking instead through the mesh of the cage to the lighted park below, the prettier of the two stared at him, and I worried for the duration of the ride that he would discover this and respond. But the ride ended without the four of us speaking. I could sense the girls turning to look at us as we walked away, waiting for us to turn, too, but Chris was already focused on the next ride. I did turn around and one of the girls pointed at Chris, motioning for me to alert him to her interest—but I pretended not to understand her until they were out of sight.

The last ride of the evening, the Prairie Boat Expedition, proved so fun that we kept repeating runs on it. Finally, the operator told us the park was closing and that this was to be our last ride. Each of the cramped, missile-like boats had room for just two people, one seated behind the other. I squeezed in front, prepared to take the brunt of the splash at the end of the ride. As the vessel was cranked up the rise, its slow chain-rattling ascent meant to heighten the fear and drama, I could feel Chris’s breath on my neck. We were wet from our previous runs, and the wind chilled us. I started to lean back, giving into the incline, wondering if I would have the courage to have my body meet Chris’s chest. I stopped before I felt him. Chris had noticed my movement and said, “It’s okay, you can do that.”

And, yet, I didn’t. I leaned forward again, gripping the dashboard of the boat until the curtain of water at impact draped over us, effectively bringing the scene to an end. Had I leaned against Chris, all of my yearnings might finally have been realized. Or I could have been misreading of his invitation, so a gesture had the potential to undo our friendship. Perhaps he was merely offering a way for me to get less wet when our boat hit the basin of water at the bottom, or maybe he figured my leaning back would give us an aerodynamic edge and speed up our progress down the final shoot. Or, perhaps, he was calling for an affection denied him during his year away from home, living as a border in a room at the top of an old, spooky house.

I knew then that I wanted to have the memory of being in love with someone at that point in life, and I had secured it. I never saw Chris again, and even though I didn’t know that would be the case when he left after graduation, I was happy to watch, over and over, a version of him on a screen that made him bigger than life. He had been my partner for one-on-one play, and the whistle had never sounded to stop it.

Discussion1 Comment

David Masello’s memory piece was such a beautiful piece of writing. Robby Benson became an important additon to David’s life. And he also had a real-life counterpart in his real best friend, Chris. Perhaps he was able to experience Robby Benson in a way that he couldn’t experience his friend, Chris. But he does seem to have come close in at least two sexually-tinged encournters. Sometimes, what we feel for a movie star can be so easily transferred from a real-life obsession. If David and Chris had become a part of each other’s lives, perhaps Robby Benson would not be such a dynamic and lingering memory. In David’s mind, Robby Benson probably represents what might’ve been for him and Chris. It’s just a fantastic piece on the importance of movie stars in our lives. David lives on, Chris lives on – and Robby Benson is probably THE BEST OF IT.